How the Madisonian Vision of Our Constitution Can Help Make America Great Again

When thinking through what’s wrong with contemporary American politics and culture, I’ve been heavily influenced by Yuval Levin. He has a written a number of thoughtful books, including The Fractured Republic: Renewing America's Social Contract in the Age of Individualism and A Time to Build: From Family and Community to Congress and the Campus, How Recommitting to Our Institutions Can Revive the American Dream. Four months ago, Levin released American Covenant: How the Constitution Unified Our Nation—and Could Again. In this book, Levin lays out a framework for how we can lower the temperature of our political debates.

A big part of our current problem, according to Levin, is that we treat the presidency as if we were in a parliamentary system. Every four years, candidates on both sides of the aisle make bold claims of taking action on “Day One.” But it isn’t just the president who earns a mandate. Members of the Senate and the House of Representatives win mandates too. In parliamentary systems, by contrast, the ruling majority, led by the prime minister, gets to wield power easily even if the ruling party (or coalition) only wins a bare majority of 50.1% of the vote.

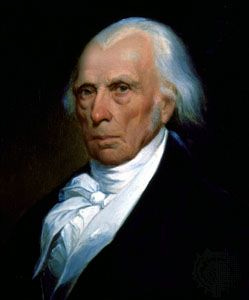

We are different than other democracies systems in other key ways. For example, our James Madison-designed system is unique in that we have three separate branches of government—the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary—that push and pull against one another horizontally and that we distribute power vertically between the federal government and the fifty states. Plus, within the fifty states, we further divide power between state capitals and local municipalities. As Yuval Levin explains, “The mix of institutions in our system and the different ways in which officials are elected and appointed within them means that we rarely have simple and durable majorities. This reality can make our debates feel frustrating at times, because we must face opposing views in our society, even when our side wins big elections.”

We will improve our politics and culture if we celebrate, rather than try to change, the fact that our system denies power to narrow majorities. Also, we will improve things if we work to make the legislature the central institution of government.

You may have heard about the three branches of government being “coequal.” But that is wrong. The Founders wanted Congress to be supreme. They gave the power of the purse to Congress, and they gave it the power to declare war. Moreover, while none of the other branches can fire a member of Congress, Congress has the power to impeach and remove presidents and judges. As Jonah Goldberg writes, “The word coequal appears only eight times in the Federalist Papers. Not once does it say that the three branches of the federal government are coequal. They reserved that term to describe the standing of the federal government to the states or the relationship between the House and Senate.”

So how did we get to a place where the president is at the center of our politics and the legislature is sidelined? To answer this question, we need to consider the birth of the Progressive movement.

Back in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, immigrants were flooding into Ellis Island and urban poverty was a huge problem. Corporations were growing in economic power and robber barons, such as Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, and John D. Rockefeller, were wielding influence in unprecedented ways. As a result, many intellectuals became disenchanted with the Madisonian structure that distributed power horizontally and vertically. These reformers wanted to take authority away from Congress and the states and place more power in the executive branch.

Writing in the “Political Science Quarterly” in 1887, Princeton University professor Woodrow Wilson explained that government becomes “irresponsible” when its “power is divided.” Twenty years later, Wilson argued that government is a “living thing” and that “no living thing can have its organs offset each other as checks and live." When he became president, Wilson centralized power in the White House. Teddy Roosevelt, meanwhile, pushed for a “new nationalism” that rejected “the over-division of governmental powers.” Also, in the early 20th century, Herbert Croly and Walter Weyl founded an influential magazine called The New Republic. Croly and Weyl chose this name because they wanted to create a “new republic” unencumbered by checks and balances. In short, as Yuval Levin explains, Progressives pushed for a more centralized approach to governance that would empower presidents to govern with far fewer constraints. Unlike the Madisonian vision, which placed Congress at the center, the Progressives thought that the greater consolidation of power under a president would yield a more united society.

Today, Congress isn’t getting much done. It’s a problem for sure. But Levin asks the important question: Should we promote reforms (like eliminating the filibuster) that will make cross-partisan accommodation less necessary? Or should we promote reforms that make cross-partisan accommodation more necessary?

Levin argues that it is only in Congress where negotiation between different factions in America can take place. If we don’t deal with our differences in Congress, our divisions will spill out to other parts of our society. He writes, “When Congress breaks down and the presidency, the bureaucracy and the courts take over, our implicit model of political action and social change gradually transforms into a less accommodation and leaves us more inclined to think of politics in winner-take-all terms and less inclined to seek compromise.” Unfortunately, we can’t work through our disagreements in Congress if Congress is broken.

Why is Congress so broken?

James Madison knew that politicians would be ambitious, and so he insisted on a system that would encourage ambition to counter ambition. The expectation was that members of the House of Representatives would be ambitious to guard the power of the House and that members of the Senate would be ambitious to guard the power of the Senate. Madison and the Founders never imagined that politicians in the House and Senate would lack ambition to use their political power but, instead, would be ambitious to become celebrities and television pundits. As Levin writes, “Traditionally, winning an election to Congress has meant winning a seat at the negotiating table, where you can represent the interests and priorities of your voters. Increasingly, it has come instead to mean winning a prominent platform for performative outrage.”

While the Framers never foresaw how the creation of television might deform our politics, Neil Postman did and wrote about it in Amusing Ourselves to Death. In this book from forty years ago, Postman predicted that television would transform public discourse away from serious debate and toward entertainment and that it would reduce complex issues to sound bites. He foresaw a world where politicians would be chosen more for their appeal as media figures rather than for their capacity to govern effectively. Social media has only made the problem worse.

But it isn’t just television and social media that’s the problem. As Yuval Levin points out, “One reason Congress now fails to mold its members into legislators is that the institution is already too centralized in the hands of party leaders, so that many backbenchers have no substantive legislative work toward which they might channel their ambitions.” Another issue is that members of Congress now perceive the voters in their primaries (who tend not to be too interested in compromise), rather than their constituents more generally, as their key audience.

It’s not practical to return to an era of smoke filled rooms where party bosses call the shots, but ranked-choice voting in primaries could help. In the ranked-choice voting system, voters mark multiple candidates in order of preference and then have their vote count on behalf of their second or third choice if their first or second choice is not among the top vote getters. States and localities are experimenting with RCV, and it is possible that this system will incentivize candidates to broaden their appeal.

Some argue that nonpartisan redistricting commissions might reduce the number of deep red and deep blue political districts that incentivize playing-to-the-base behavior, but the larger problem is that we are self-sorting ourselves, a trend which Bill Bishop first identified in The Big Sort and has only gotten worse in recent years. Progressives are choosing to live near other Progressives and Conservatives are doing the same. It used to be rare to find an interracial couple. Now it’s rare to find a politically mixed-marriage. My marriage to Jackie is the exception to the rule.

We can’t easily turn off the self-sorting, and we also can’t rewind the clock on television and social media. But we can take the C-Span cameras out of Congress.

As Yuval Levin writes, “Cameras have turned all of Congress’ deliberative spaces into performative spaces, leaving less and less room and time for members to speak and work in private. There has obviously always been grandstanding in Congress, but the omnipresence of cameras has taken that vice to new lows. To make matters worse, the ubiquity of cameras has attracted cadres of members who understand public performance as the essence of the job.”

The bottom line is that negotiation can’t happen in public view. Yuval argues for private working sessions devoted to floating proposals and hammering out legislative deals. He also argues that C-Span should transition away from televising hearings and. instead, host formal conversations among members of key committees from both parties. “In such a setting,” Levin writes, “the presence of television cameras would actually discourage grandstanding. It would also help members get in the habit of speaking respectfully with each other across party lines.”

It isn’t just that we need to get rid of the cameras and reform the candidate selection process. When we think about the Madisonian approach to making America great, we need treasure localism as a path to social peace. As Levin writes, “The Constitution’s guarantee of republican representative institutions in every state and of the freedom to move from place to place in our society makes it possible to give states (and within states, to give localities) a lot of leeway when it comes to determining the character of different political communities.”

Of course, there are limits to what local majorities should be able to do. It took America way too long to ban slavery and, later, Jim Crow. And it is true, as Yuval Levin points out, that “the moral convictions of the American people may lead the nation to conclude that further matters must be resolved nationally.” But, to the greatest extent possible, we should encourage diverse modes of self-government at the local level.

The Madisonian approach to governance protects individuals from oppression by the communities of which they are a part, but it also protects communities from oppression by political majorities in the larger society. Consider modern debates over gender ideology. Big arguments are taking place about whether biological men can participate in women’s sports and about whether gender transitions can be publicly funded and about whether children can change their gender in school and the school can hide this information from their parents. The Madisonian approach allows for individuals to pursue their own definition of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” This means that transgender individuals like Caitlyn Jenner and Harper Steele can live out their freedom. But it also means, for example, that minority communities of religious Jews, who believe God created men and women as distinct genders, have the right to practice their faith in the public square. Tolerance is a two-way street.

In the Madisonian world, outcomes will usually be less than ideal. Societal change occurs slowly. It’s often two steps forward and one step back. As Levin writes, “It’s easy to get angry at the slow of negotiated settlements and the stalemate. That placid pace of our system of government is frequently aggravating, of course, but it is crucial to the capacity of a politics of negotiation.”

Given America’s ethnic, religious, and ideological diversity, our ability to coexist is a remarkable miracle. Yuval Levin argues that, given this diversity, we should have a lot gratitude to live in a peaceful society where people practice radically different religions and don’t kill each other over these differences. I pray that our experiment in self-governance can continue, but I’m very worried that things are going to get violent over the next few months. If we make it through this next election and have a peaceful transfer of power, we should feel a tremendous amount of gratitude. Something to think about in a few weeks at the Thanksgiving table.