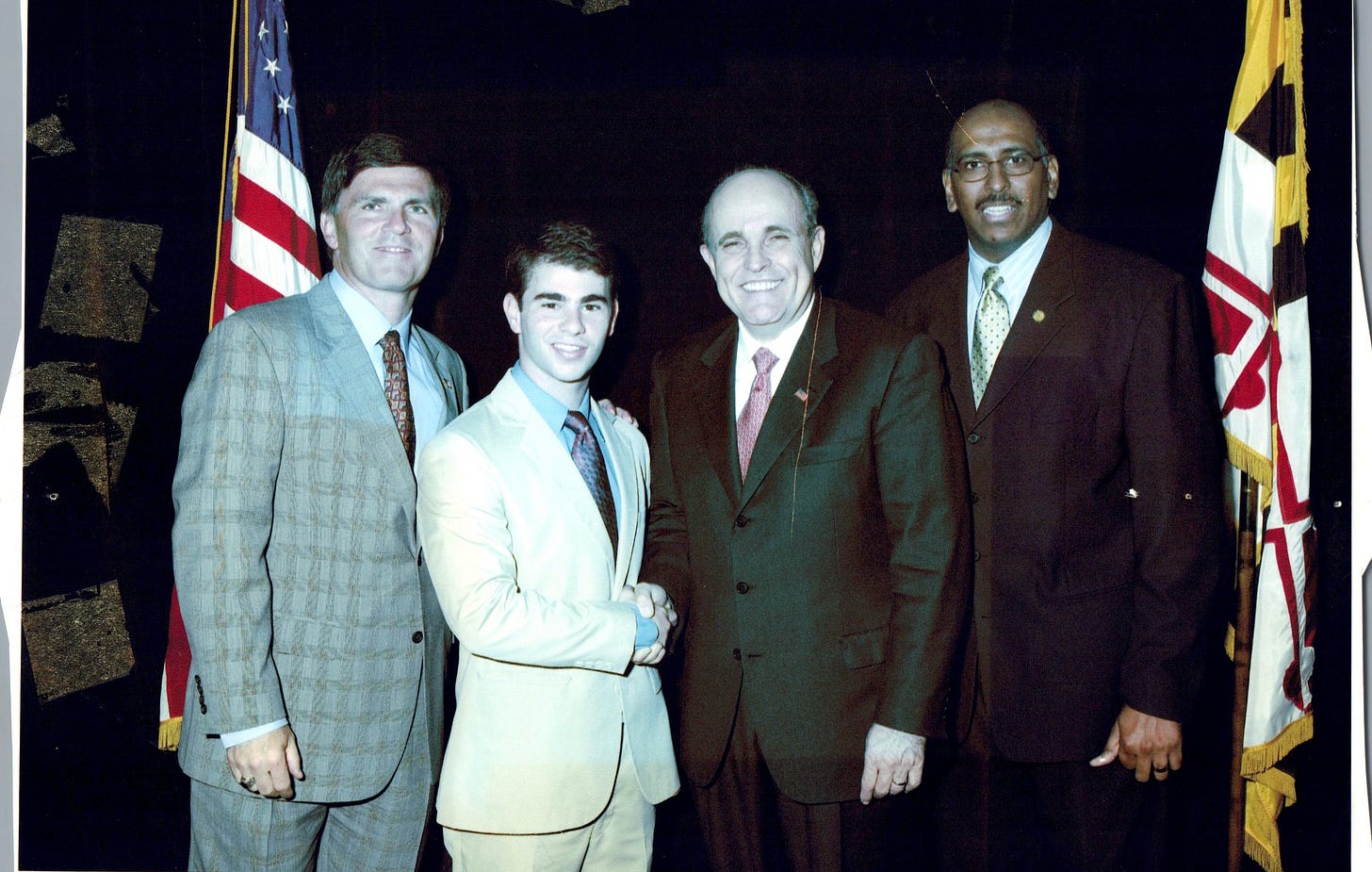

Me, Rudy Giuliani, and Crime in New York City

This photo is from 2002. I met Rudy while working on my first political campaign. Back then, he was a hero and had been recently named Time magazine’s person of the year for his leadership on and after 9/11. How things have changed! Giuliani is better known now for spewing lies about the 2020 election while makeup dripped off his face. Indeed, one might say that Rudy has changed as much over the last two decades as New York City changed during Giuliani’s two terms as mayor.

It’s hard to believe but Times Square used to be overrun with prostitutes, pimps, and drug dealers, and “Squeegee men” would intimidate drivers into giving them money. The subways were covered in graffiti, and it was estimated that people would jump over the turnstiles to the tune of 250,000 occurrences a day.

For those trying to imagine what a disaster New York City used to be, it can help to read the cover story from Time’s issue on the “rotting of the Big Apple.” For another time capsule, check out David Sale’s reporting in the Washington Post from September 22, 1989. Sale tells stories of pervasive signs in the windows of cars with “No Radio, Nothing in Trunk” or “No Radio, Already Stolen.” According to Sale, “Sometimes the signs are store bought; others are scribbled on cardboard or plain paper. These signs have sprouted up because, for the most part, the police and the greater criminal justice system have viewed car vandalism as a relatively minor crime against property.”

In their influential article in The Atlantic Monthly about “broken windows” theory, George Kelling and James Q. Wilson argued that government’s inability to control even a minor crime like graffiti signaled to citizens that it certainly couldn’t handle more serious ones. So the first step to dealing with more serious violence was to focus on turnstile jumping, noise pollution, drug dealing, public urination, etc. Taking a page from Kelling and Wilson, Giuliani and his team, led by police commissioner William Bratton, started by arresting the “Squeege men” for jaywalking. When they went after turnstile jumpers, the police found that one out of every seven people that was arrested for fare evasion was wanted on a warrant, and one out of every 21 was carrying some type of weapon. These public efforts to confront disorder changed the tone in New York City, paving the way for a safer and more livable environment. When I interned on Giuliani’s presidential campaign in 2007, I sifted through FBI data to show how NYC had the steepest drop in crime among all major American cities in the 1990s.

To be sure, the “broken windows” approach to policing has its detractors. In 2020, some Democrats in the House of Representatives introduced a resolution that blamed broken windows for “mass incarceration that disproportionately impacts black and brown people.” But I think the evidence is overwhelming that the concept is real. Kees Keizer, a researcher from the Netherlands, compared the behavior of people under artificial conditions of order and disorder. In one experiment, Keizer placed an envelope conspicuously containing five euros in a mailbox. When the mailbox was clean, 13 percent of people who passed it stole the money; when it was covered with graffiti, 27 percent took it. In short, disorderly conditions encourage more serious levels of disorderly behavior, which then leads to more criminal behavior.

When I read about the New York of the 1970s and 1980s, I wonder: If Rudy never got elected mayor, would my sister have moved to NYC when she graduated college and began her teaching career? Would my brother have moved there to pursue his PhD program? Would I have met my wife, Jackie, and would we would have moved to Queens four months ago?

I’m doubtful any of this would have happened.

A few weeks ago, Jackie and I visited the Bryant Park Holiday Market to get delicious hot chocolate from No Chewing Allowed. (This pop-up place places a rich chocolate truffle on the bottom of the cup.) We also bought pottery from Jackie’s coworker’s husband. There were nice bathrooms and a skating rink and thousands of visitors. It’s hard to imagine that this park was once overrun with drug dealing and criminal activity.

I love the NYC renaissance in the 1990s, but I wonder about the dark side that wasn’t as visible. What would have happened if every person in NYC had a camera on their phone in the 1990s? If iPhones existed back then, I think we would know many more names of Black men who had suffered mistreatment by the police. In recent years there have been people like Eric Garner and George Floyd who have been killed by cops. One name I now know is Shabaka Shakur, whom I saw speak this past September. Though not a victim of police brutality, he was a victim of police misconduct.

In 1988, Shabaka Shakur, age 24, was arrested after two of his friends were shot and killed in Brooklyn. Though Shakur had two alibi witnesses and the gun found near the crime scene could not be linked to him, he was sentenced to 20 years.

While incarcerated, Shakur met another man, Derrick Hamilton, who had been wrongfully convicted of a murder in Brooklyn. Hamilton and Shakur spent many hours in the prison library researching the law with the hopes of proving their innocence. As they conversed, they came to realize that they had been sent to prison by the same person: Detective Louis Scarcella.

Scarcella was a respected detective of the Brooklyn North homicide squad and worked on more than 70 murder cases in his nearly three decades as a member of the NYPD. Shakur explained in his talk that Scarcella was known as “The Closer,” since he had a “knack” for cracking tough cases. But it turned out that Scarcella had a track record of fabricating testimony in multiple instances, including in Shakur’s case. Scarcella told the judge that Shakur had confessed to the murder.

Shakur’s wrongful imprisonment had nothing to do with Broken Windows policing but it is an example of how cops aren’t perfect. I’m very much a “w Blue” and “Blue Lives Matter" kind of guy, but it’s important to recognize how police can make mistakes and even act in malicious ways. In short, police officers aren’t always the ideal public servants.

While acknowledging that police aren’t always the good guys, there are downsides to protesting the police. Charles Fain Lehman, a fellow at the Manhattan Institute who studies crime and drug policy, argues that large-scale protests against the police lead to reductions in police officer activity and increases in serious violent crime. When we send a message to the cops that they should be doing less, the police respond by being less proactive and leave the profession altogether. We can’t take our police departments for granted.

As I wrote about a few months ago, fewer people are applying to become police officers and more officers are retiring. In New York City, staffing issues have resulted in higher response times for many kinds of service calls. As Rafael Mangual writes in the New York Post, in October 2022, the response times for critical, serious, and noncritical calls had risen 38 percent, 43 percent, and 52 percent, respectively, since October 2019. And according to a report released several months ago, the average response time for NYPD officers to arrive at the scene of a reported crime has reached its highest level in years. As troubling is that a recent report from the American Enterprise Institute found that, between 2013 and 2022, arrests for quality-of-life offenses—fare evasion, lewd behavior, vandalism, loitering, public drinking and intoxication—fell 74 percent in New York City. I’ve recently read about the return of "Squeegee men" and turnstile jumping.

As a new New York resident, I’m excited to vote for a new mayor this year. A top issue for me is not only the prevention of crime and disorder but also of the need for justice and equal treatment under the law. On these topics, I think of my many conversations with Jackie over the last several years.

On the one hand, like many progressives, she has, at times, spoken negatively about the police. On the other hand, she also expressed a tremendous amount of gratitude that a police officer was in the subway car when she travelled back from Penn Station late at night in November. Like her, I can be frustrated with troubling police behavior while also recognizing their importance to society. I’m incredibly fearful of a New York City in which the police step back from Broken Windows policing, because I think it will lead to an increase of more violent crimes. At the end of the day, I’m not a gun owner and I don’t have a concealed weapons permit. If I’m in trouble, I’m depending on the men and women who put their lives on the line to protect us.